This passage was appeared as a dedication to Dr. Cross in a sexuality education manual I co-authored, Older, Wiser, Sexually Smarter: 30 Sex Ed Lessons for Adults Only. (Brick, et al., 2009) It serves as an ideal introduction for addressing the importance of doctors talking about sex.

Like the Skin Horse, older adults might think of themselves as shabby. Certainly society reinforces the message that the sexuality of elders is not to be taken seriously. Witness the appearance of 90-year-old Betty White on “Saturday Night Live” discussing her “muffin” to the roars of audience laughter. The bit just doesn’t work if it is delivered by someone who is 30 or 40-something. But older folks? There’s so much “material” that our sex ed manual devoted an entire lesson on teaching with jokes. Here is one of my favorites, which I read for the medical students.

A doctor asked an 85 year old man for a sperm count as part of his annual exam. The doctor gave him a jar and said, “Take this jar home and bring back a semen sample tomorrow.”

The next day the man returned to the doctor’s office and gave him the jar – which was clean and empty. The doctor asked what happened, and the man explained, “Well, doc, it’s like this. First I tried with my right hand, but nothing. Then I tried with my left hand, but still nothing. Then I asked my wife for help. She tried with her right hand, then with her left, still nothing. She tried with her mouth, first with the teeth in, then with the teeth out, still nothing. We even called up Arleen, the lady next door, and she tried too – first with both hands, then an armpit, and she even tried squeezin’ it between her knees, but still nothing.”

The doctor was shocked, “You asked your neighbor?”

“Yep! None of us could get the jar open.”

After some hesitated laughter from the students (“Is he going to be mad if we laugh?”) we got to the root of what makes the joke funny. It rides on the premise that older people enjoying healthy sexual behaviors is laughable. A man masturbating at age 85?! Many people — including doctors — wouldn’t even consider that a real possibility, even though research tells us that up to 63% of men ages 57 to 85 reported masturbating during the past year. Elder oral sex? It might prove a lot less taxing than missionary-style intercourse, but the collective images many of us share of sweet old grandma and grandpa do not make any allowances for their non-procreative sex expression. Indeed, when I survey undergrads about how “sexually active” they imagine themselves being 40 years from now, they almost universally imagine themselves as sexual studs, with many of them ranking themselves 7 or higher on a 10-point scale. When I ask them to imagine the sexual prowess of someone aged 60+ that they know, the scores drop down to 2’s and 3’s.

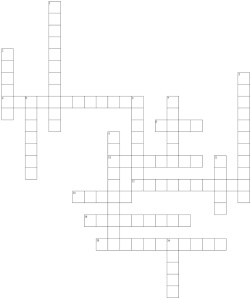

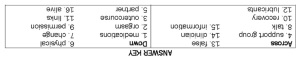

Having broken the ice, and perhaps opened a few eyes, I return the medical students to some familiar ground: sexual problems. The worlds of physicians and medical students is rightly filled with opportunities to figure out solutions to problems, and the sexual challenges of older adults deserve no less attention. The docs-in-training enjoy spending some time figuring out a crossword puzzle full of important information to know about sexuality and aging. (The handout is included at the end of this article. Try it out yourself!)

We continue by examining some of the common changes in sexual response that men and women experience as they grow older. (See Table 1.) I ask the medical students to identify one change that might cause a patient some anxiety. This is a big “Ah ha!” moment for a lot of students, such as the one who was genuinely concerned as he said, “A man who has a refractory period lasting for a day or more might think there’s something wrong with him. He might wonder why he can’t perform like he did when he was younger!” Bingo! And so we start discussing how knowledge about these changes might be more helpful than a little blue pill. Or how a supply of over-the-counter lubricants might be handy to store in one’s office. Or how a few words explaining what outercourse means might change a patient’s sex life for the better!

Table 1. Sexual changes at Mid and Later Life

Men

• Erections are not as firm, may be lost rapidly after orgasm. Penis needs more stimulation by self or partner.

• Experience of orgasm may feel different (forcefulness may lessen).

• Lubrication that appears prior to ejaculation decreases or disappears, and volume of seminal fluid (ejaculate) is reduced.

• The sensation that ejaculation is imminent may lessen or disappear.

• Refractory periods are longer (i.e., subsequent orgasms may not be possible for hours or days).

• Fertility extends well into later life so protection from unwanted pregnancy is necessary.

Women

• Sensitivity of clitoris may increase or decrease.

• Vaginal lubrication takes longer.

• Breast and nipple sensitivity may change.

• More time and stimulation is required for arousal and orgasm. Elasticity of the pelvic floor muscles (integral to orgasm) diminishes.

• Uterine contractions that are part of orgasm may become so intense that they are uncomfortable or painful.

• Fertility discontinues.

We turn to communication skills, and I give a brief explanation of an old theoretical model that is, regrettably, not taught very much in higher education programs anymore, despite its potential for communication skills-building. The model of transactional analysis was resurrected and applied to sexual decision-making by Amy Vogelaar in the guidebook Positive Encounters. (Vogelaar, 1999) While Vogelaar’s approach is steered toward communication with teens, the basic understanding of “ego states” (directive “Parent,” pleasing “Child,” and problem-solving “Adult,”) is an essential for counseling, whatever the audience. The medical students learn the importance of communicating in the non-judgmental “Adult” ego state and are ready for practice.

For the practice activity, I read this scenario:

Imagine that you are visiting with a patient whom you’ve seen many times before, but the two of you have never discussed any sexual matters. You’re not even sure if the patient is still married/partnered or dating. You know that you will be renewing one of the patient’s prescriptions, which has some side effects that might affect sexual functioning. You mentioned this possibility when the patient first started taking the medication years ago, but you’ve never asked about sexual side effects. You think that the patient might not be taking the medication consistently, and wonder if that is the reason.

The students write the first thing they would say to their patients. After everyone is finished writing, I ask them to pass their papers to the person to their right. Now everyone adopts the role of the patient, and writes down a response to their physicians. As patients, I ask them to make up what’s “really going on” and decide how much they want to share with the physician. The responses are turned back to the left – to the original doctors – and the process continues for several rounds.

As we process the activity, a number of students report having had very helpful exchanges. I remind them that the entire activity took not more than 10 minutes, and ask them to imagine the meaningful discussions they might have with their patients in less time, when writing is not part of the activity!

I also remind the students at UMDNJ that they are fortunate. Most medical students do not have formal opportunities to learn how to talk with their patients about sexual issues. (Barrett & Rand, 2009) So I ask the students to examine the recommendations for doctors from ordinary adults that can be found in Table 2. I ask them to evaluate the advice in terms of its usefulness for other medical students or doctors. The future docs are genuinely appreciative of this advice, and give the list an enthusiastic “thumbs up”, as they leave the workshop feeling confident to speak with older patients about sex.

Table 2. Great Ideas for Physicians

1. Ask about sex and intimacy during routine exams — both male and female older adults may be reluctant to bring up the topic, but will gladly discuss if asked.

2. Have a caring — not only clinical — attitude toward patients.

3. Try to avoid making assumptions about a patient’s sexual orientation, or how sexually active s/he might be.

4. Recognize the diversity of religious and cultural traditions that affect how people express their sexuality. Try to avoid judging, moralizing, or pushing religious beliefs on patients.

5. Watch for subtle hints patients may be giving you to discuss sexual concerns.

6. Encourage patients to speak openly about sexuality. Be patient with expressed concerns and answer questions honestly and openly.

7. Help patients understand that sexual desires, concerns, and issues are normal. Avoid minimizing patients’ concerns.

8. Discuss the benefits of sexual pleasure, including masturbation.

9. Suggest that couples cuddle, exchange massages, and shower together to rekindle the sexual connection that originally brought them together.

10. Teach pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises as a way to increase sexual pleasure, as well as for incontinence prevention.

11. Explain how one might make sexual activity easier if physical problems exist.

12. Give information on what to do about decreases in sexual desire and vaginal dryness.

13. Discuss the pros, cons, and sexual side effects of medications, as well as non-drug approaches to sex-related problems.

14. Recognize the growing rates of sexually transmitted infections among older adults, including HIV. Provide accurate, current information.

15. If appropriate, consider bringing adult children into the discussion to help them understand, respect, and support their parent’s sexuality.

16. Provide referrals, books, videos, and other materials to patients regarding sex and intimacy.

17. Request and take advantage of continuing education about sexuality and older adults. Share valuable information related to sexuality with your colleagues.

References

Barrett, B. & Rand, M. (2009). “‘Sexual Health Assessment’ for Mental Health and Medical Practitioners: Teaching Notes,” American Journal of Sexuality Education, 4(1):16-27.

Brick, P., Lunquist, J., Sandak, A. & Taverner, B. (2009). Older, Wiser, Sexually Smarter: 30 Sex Ed Lessons for Adults Only. Morristown, NJ: The Center for Family Life Education.

Vogelaar, A. (1999). Positive Encounters: Talking One-to-One with Teens about Contraceptive and Safer Sex Decisions. Morristown, NJ: The Center for Family Life Education.

PUZZLING SEXUAL PROBLEMS